The Count of Monte Cristo

by Alexandre Dumas, père

Warning: This review and analysis include several spoilers. Read at your own risk.

Style and Substance

The writing in Alexandre Dumas’ historical French novel, relating a 19th-century tale of injustice and revenge, can be long winded. Readers might expect this when noting that an “unabridged” version ranges between 1100 and 1400 pages. With so much space consumed, we might suppose this writer who loved his craft was tempted into ostentation. Perhaps he was.

However, I wouldn’t call his style flowery; a tempted Dumas exhibits self-control. Understated and enticing, the author’s abundant wit, along with great storytelling and readable prose, justify the length of the text. Truly.

I finished this book club selection more than a month before our February meeting, quite the feat considering how often I don’t finish on time. Yes, I started before our last meeting about a single Agatha Christie short story, but never mind.

A suspenseful page-turner for most of its fecund pages, The Count of Monte Cristo kept me reading steadily to learn the fates of characters set aside for long, overlapping periods. My circumstances helped, but Dumas helped more.

Rooted in European history, the settings span a 25-year period of the early 1800s and explore diverse locations from sea and prison to Rome, Paris, and the French countryside. At the story’s fulcrum is the question of political loyalties and their implications. Early shifts in power between Royalists and Bonapartists animate the lever that decides the ground on which central characters begin their journeys.

The plot is intricate and well organized, and the story proves emotionally dynamic, replete with dramatic irony. Rhythmic flow springs from engaging dialogue, which, beside measured descriptive text, renders Monte Cristo a delightful, theatrical melodrama. Its film adaptations attest to this strength with their number.

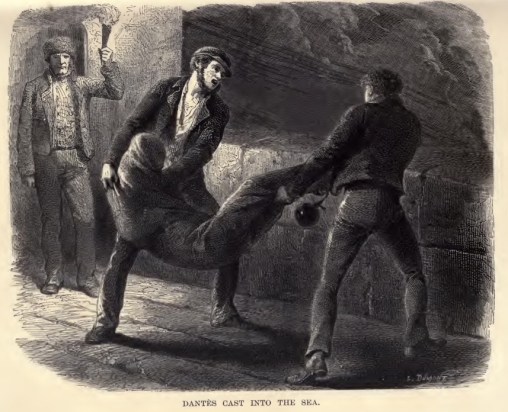

“Dantes Cast into the Sea” by French artist Dumont. George Routledge and Sons edition, 1888

Genre, or Who This Book Is For

My first, unspoiled reading never brought tears, drew audible gasps (maybe some silent ones), shocked me, or provoked any wild laughter. In that way, I see it as a steady, well-written, well-told yarn composed of entertaining threads. It is more dark, sweeping Romance in the Gothic tradition than affecting, relatable human drama. This fact tempered my enthusiasm somewhat, as I tend to prefer the latter.

Intrigue, mystery, crime, adventure–all in the particular context of early 1800s Continental politics and cultures–overshadow character complexity and intimacy despite dozens of highly emotional moments. Sadly, there are no kisses lip to lip, let alone sex scenes; sexual suggestiveness is rare and subtle.

Perhaps Victorian in those respects, the book offers some extreme violence, ample cold-blooded murder, and one instance where an unconscious maiden signifies rape. Several incidents are told as stories within the story, but such elements serve to emphasize the grisly tragedies and grotesque fascinations comprising the tale.

Specific Critiques and Praise

Among its flaws, The Count of Monte Cristo tends to telegraph plot points. Thus, prolonged suspense meets the anticlimax of predictable, but satisfying, outcomes. We could attribute this forecasting effect in part to the amount of space and time provided for the reader to guess results correctly, but it is noticeable.

[Second warning: If you’ve never read this book but think you might want to, leave this post now and go read it!]

Still, I felt great moral and literary satisfaction in anticipating the villains’ comeuppance. Then, the collateral damage is realistic and heart rending, dispelling any notion of a surgically precise wrath of God. Lingering questions about the fates of key characters also felt appropriate, particularly concerning Benedetto. As we leave him, we suspect he just might get away with his crimes.

The reader gains significant insight into more than half a dozen characters, sympathizing with their situations. By this method, Dumas succeeds in conveying the imperfect nature of vigilante justice (or any justice) as each major villain meets a punishment that may not match the severity or nature if his crime. The costs of vengeance are dear. Given the paths before these ends, the final choices and turns the antagonists make seem to befit their personalities, also well developed.

By contrast, I found the main character surprisingly underdeveloped for so long a work and despite, or perhaps because of, the different characters he embodies. Edmond Dantès’ journey is remarkable early on and leading into his manifold vengeance. The changes starting to take shape in the climax also work well, but the ending felt rushed. Dantès’ reflections seem insufficient, his remorse and renewed questing half hearted, and his love for his ward lukewarm and a bit convenient.

[Third and final warning: I really mean it this time – Turn back now or skip to the summary below, or suffer the consequences!]

One can imagine Dantès’ moral education continuing beyond the fifth volume of the story, along with the revival of his will to live and start again. I don’t personally need a neatly wrapped ending. Yet, if that emphasis on waiting and hoping was the author’s intent for Dantès as much as for other characters, I would have preferred hints of a more precarious future happiness for our primary hero, more of a sense that the next climb may be just as long and steep as the last.

For Love of Money

Other trouble comes in the author’s apparent emphasis on needing a seemingly limitless fortune to possess true, full freedom and happiness. This notion meets no significant challenge anywhere in the story, which I found strange, if not quite disappointing. Reinforcing this sentiment is the unmitigated misery associated with every example of poverty or even humble means. Dumas might look upon the poor as inherently noble creatures, morally superior, a Romantic vision, but he leaves no doubt that everyone from prince to pauper prefers, and even needs, substantial wealth. Such assumptions irritate.

The exceptions are the slaves the Count owns; Dumas portrays the happiness of Ali and Haydée to be as incandescent as their devotion is supreme. They hardly count, for they are completely dependent, without their own money, and thus without authentic agency. The author seems to doubt that even a single, independent Frenchman could be happy in this time and place without one of the following conditions: possessing great fortune or knowing the security of directly and loyally serving (or being a beneficiary of) a person of great fortune and benevolence, such as the Count of Monte Cristo.

Evidence accrues of the author’s money love. The vast majority of focus characters are members of high society and the wealthy elite, many of superior education, notable beauty, close royal connections, or distinguishing experience. Yet nowhere do riches serve as an obvious corrupting force, except in the most obvious, a priori cases of the antagonists.

The young people cradled in luxury from birth–Albert, Eugénie–adapt swiftly to financial uncertainty, if not to real or projected financial loss. Each is strong of mind, and each charges ahead with definitive plans. Their apparent lack of greed seems plausible, but how long will they last? On the contrary, how will the two most worthy, noble, and innocent characters (hint: not Albert or Eugénie) avoid their lives’ ruination upon acquiring an incalculable fortune?

Currency for the Count

During the rising action, as he operates like some other-worldly creature, at least the Count’s near immunity to the ill effects of being filthy rich seems reasonable. The immensity of the treasure he acquires coupled with the depth of the misery he has suffered accounts for it. There is no room for covetousness, for there is no need. His vision is fixed not on indulging his chosen life of opulence–for his jaded soul can hardly enjoy it–but on using it for convoluted, comprehensive payback.

It is in the name of this sophisticated vengeance for genuine wrongs against him that the Count wields his fortune, education, disguises, and cunning like a four-flanged mace of justice. It is only after his perceived atonement for such absolute revenge that the Count is finally ready to relinquish his wealth and the power and esteem it awarded him. As a result, he believes he needed the money only for the scores he had to settle, but without money going forward, his status and influence will fade.

The question is, Can he indeed adjust to this new reality? For an author whose characters so unilaterally and fervently depend upon prolific capitalism for their happiness, it would seem doubtful. It makes me curious to learn about the life of Alexandre Dumas (of which I currently know nothing), to seek a reason for this.

Revenge? What’s That?

Since the reader never has the chance to observe the changes in either the man who gives away his “first-rate” fortune or those who receive it–changes either in those who lose all they had or in those who squirrel away a buffer against such loss–the consequences of these shifts remain open ended. Despite the age difference between the Count and the younger people, all seem to be of a more flexible generation than their parents are regarding money, status, and survival.

What may be most telling is that none of the villains (1 of the 3 perhaps) truly suffers for very long the consequences of their greed and evil. Each escapes a traditional punishment the reader might think they deserve, whether doing so by their own free will or decidedly not. We never get to see them struggle for any notable duration without money, without status, without family.

They suffer in other ways, many established without the Count’s interference long before he catches up with them; most of it they have done to themselves. The prospect of loss terrifies them and they sustain heavy blows. However, no one reaches, before story’s end, the degree or longevity of deprivation and sorrow that Edmond Dantès has known at their hands.

An epilogue assuring the reader that the evildoers will all receive and experience what they deserve–whether in life or in death–might have been soothing. Without it, we can only guess, “wait and hope” that at least one of them does.

Mercédès

As to patriarchal double standards, I found the Count, if not Dumas, to be harsh in accusing and punishing Mercédès, Edmond’s betrothed before his imprisonment. She is also harsh in judging herself. The woman who becomes Countess de Morcerf, though marrying Edmond’s rival and persecutor, was technically as innocent as Valentine and Maximilien. Disgraced and poor in the end, she is convent bound as her son leaves for military service. The weight of having lost and again losing Edmond is her greatest regret, and rightly so, but it is through no fault of her own in either instance.

Her ignorance and naive perspective of wrongdoing matches Edmond’s as he begins his time in jail, and Mercédès does what she can to atone in the end. Yet the reader is left with the sense that her punishment is deserved, she has not done enough, and she was even a sort of prostitute under the circumstances–all of which is hyperbole. First, how could she have known? Second, what should she have done differently while kept in ignorance?

Mercédès nursed Edmond’s ailing father to his dying day, continued to appeal to the government for news of Edmond, and then made the best of loss and a loveless marriage, sought continuously to better herself, raised a worthy child, and finally relinquished all her ill-gotten gains.

Among all central characters, as Countess de Morcerf, Mercédès alone never seeks to harm anyone, only to save them. More than Haydée, who avenges her father, if not more than Valentine, who avenges no one directly, Mercédès is in fact among the most saintly of the story’s women. Also, because she is so very far superior to both Baroness Danglars and Madame de Villefort, the Countess de Morcerf receives more than unjust treatment.

The unwarranted nature and degree of Mercédès’ eventual suffering approach those of Edmond’s initial suffering. What is that one saying about those we love most? With nothing but vengeful hatred in Edmond’s heart as he enacts his plans, he has doomed his first love, Mercédès, from the start. Perhaps instead of “Frailty, thy name is woman” (Hamlet), the Shakespeare quotation Edmond should have studied and remembered is “The quality of mercy is not strain’d” (Merchant of Venice).

Summary Review

The Count of Monte Cristo is a robust, culturally observant work that explores the mysteries and ironies of destiny. Absorbing characters take shape at a good pace for the story’s length. There is clear, abundant evidence of the skill, the care–in short, the investment–applied by author Alexandre Dumas, père (senior). Although I would have preferred a more detailed look into the title character’s mind and the lessons he learns, the novel, like the Count himself, has earned its place among the classics. I doubt I’ll ever re-read the book entirely, but I imagine returning on occasion to dip into its turbulent, colorful, and ambitious pages.

My rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars.

Translation and Abridgement (No Spoilers)

À propos of length and language, I found no fully reliable, consistently clear, and high-quality English translation among the five versions I sampled while first reading and listening to the story. The Robin Buss translation published by Penguin Classics, though widely preferred and lauded, may be more complete than other unabridged editions, but I found the diction too contemporary, the phrasing overwrought, and the writing generally less elegant than in other editions.

Furthermore, while at times wrinkling my forehead in puzzlement at the Buss translation, I found the text of the Oxford World’s Classics 2008 edition–and even more so of the David Clarke Librivox recording and very similar Gutenberg Project epub ebook–to be more accurate, more logical and appropriate to story context, and more understandable in several instances.

I doubt this divergent assessment has anything to do with my having studied French for 8 years. It probably has more to do with my preferences for archaic diction, unusual syntax, and general clarity. A treasured French study background increased my enjoyment in part due to my understanding of the untranslated French expressions, such as “Pardieu!” (literally “By God” but meaning “Of course!” or “Indeed!”), but any astute reader can gather meaning from context.

Incidentally, David Clarke does a fabulous job with theatricality, French and Italian accents, male and female registers of voice, distinguishing main character voices, clear and consistent projection, and excellent articulation. Aside from occasional mispronunciations, Clarke may have stumbled once or twice in 117 chapters in the Librivox recording. Highly recommended. My having blended listening to recordings with reading ebooks and print copies is largely what allowed me to keep my momentum and finish this massive book quickly.

The Gutenberg file uses the 1888 illustrated (and non-illustrated) George Routledge and Sons edition. I thoroughly enjoyed the illustrations by various French artists of the period provided in the .html version of that file. The claim of Robin Buss’s work in the Penguin Classics translation is the supposed recovery of and return to nuances of the original text that had been lost in earlier editions, and I can see some of that happening as well.

The comparable heft of the Modern Library Classics edition suggests little to no abridgement, but I found it makes noticeable, unnecessary cuts, at least to descriptive text in the few parts I bothered to read.

At any rate, we must allow that some flaws resulting from translation could be due to the original author’s style and diction in French as well. I recommend reading an unabridged edition if you read the book at all. Furthermore, if you are fluent, I feel confident, without having read it myself, in advising you to read the original French instead of a translation into English or other languages. Bien sur! (Pardieu!)

If you enjoyed this review, you may also like: