In reference to the Great American Read event presented by PBS and Meredith Vieira.

See also: my post about the results, America’s top choices for the Great American Read.

Like most things in our culture, in everyday life, reading is a highly personal affair. I won’t tell you which book to vote for, which book is the best novel for American readers, but I can shed some light on how and why to choose any work of fiction.

As much as individually we tend to choose to operate by the assumption that quality is subjective, there’s a difference between objective quality in any product and its capacity to meet our personal standards and preferences. Online product reviews use the rating system rather liberally, and people take liberties with the option to select only one or two stars out of five. Most products are never as bad as we perceive and make them out to be, and probably, most are rarely as good. A coffeemaker can usually perform more than adequately, even if it’s not a top competitor.

As consumers in a capitalist economy, we have the luxury of choosing the best possible model on the market for our budget. We take our coffee very seriously, after all. On the flip side, that special pillow you bought may have improved your life, but it’s not likely to be a literal lifesaver. Then again, it’s your sleep, not mine, so who am I to judge?

Entertainment products, such as books and movies, are different. It’s true there are standards according to which reviewers and awards committees hold most works of fiction, for instance, but novels in particular can be difficult to quantify, to categorize, and to size up. Experienced readers and reviewers have a greater claim to knowing the formula, if there is such a thing, that makes a great book. But with entertainment, the subjectivity factor carries more weight in the judgment of a book within society and against all other books; they’re not widgets, coffeemakers or pillows.

Sure, traditionally, their form has been mass produced—they’re made of paper and ink or bits of data—but the product itself moves beyond the assembly line. A work of literature is an experience over time, a thing of variable content in its use of ideas and language, and a journey through a story of imaginary people, places, and things. Its nexus of abstraction sets it well apart from the concrete world of electronic devices and motorized vehicles.

But reading is more than just a mental exercise. Stories take us on emotional and sometimes visceral roller coasters of reaction. Authors of books and makers of film can make people cry, laugh, gasp, shudder, scream, swoon, wretch, and more, simply by their artful, vivid use of words and pictures.

For me, reading is about making connections—between me and the author, me and the characters, my life and the setting and plot, between ideas in one story and ideas in another, between different art forms. I tend to read interactively if I’m not reading on a deadline. It’s about savoring as well as digesting, rather than simply ingesting, the art. I like to taste my food as it’s going down, getting to know its different effects on my palate, its aroma, texture, and consistency, rather than devour words like individual grains or layers of sauce—en masse with the rest of the meal.

I like to read about the author’s life, wondering about connections between the story and the life. I like to talk to the author, or myself, through margin notes, Post-It notes, and by writing about the book elsewhere (like here). I like to think about the book’s relationship to culture, to other books, to film, and even to itself. I read deliberately.

In part, that’s about remembering what I’ve read. Processing the content in multiple forms and ways ensures that I’ll retain more details, assuming those matter. On the other hand, a great book doesn’t require as much hard work. To me, a great book combines high objective quality with readability and complexity. It also takes the reader through the gamut of emotion and ideas, a panoply of interesting characters, in a captivating setting, through an unpredictable plot, with grace and style and wit. A great book provokes thought, touches the soul, and stays with the reader long after the final page is read.

By these standards, I hereby make my top choices for America’s best book, which is a different thing than America’s favorite book. The Great American Read started with a list of the 100 most popular novels in America. Although using it as a springboard for this post, I won’t remain beholden to that list’s rather narrow confines. My choices are based on reading the book, so I make no selections where I have not read. This makes my picks even more personal, as they omit what I’m otherwise sure are some gems of literature. At the same time, I’ll select my least favorite books from the GAR list and try to pinpoint the reasons why.

Drawing from both the Great American Read top 100 and my own Goodreads read books list, my top novels read are the following. They appear in alphabetical order, and some link to this blog’s reviews of each. Later, I’ll narrow it down further, but I don’t really believe in single, all-time favorites of any kind of thing. There’s simply too much out there for me, for all of us, to love.

- Absalom, Absalom! By William Faulkner

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; and, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll

- Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- Chronicles of Narnia, #1: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis

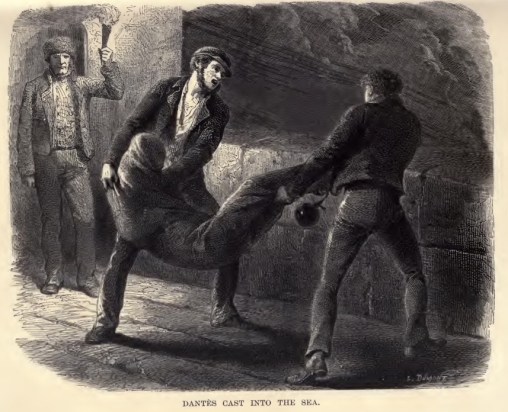

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

- The Dream of Scipio by Iain Pears

- The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

- Howards End by E. M. Forster

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

- Lord of the Flies by William Golding

- Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe

- One True Thing by Anna Quindlen

- Outlander (first book only; have yet to read books 5-8) by Diana Gabaldon

- The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

- Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Tess of the d’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

- Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

- Watership Down by Richard Adams

Which books did I find most amazing?

- War and Peace

- Outlander

- In Cold Blood

- Gulliver’s Travels

- Brave New World

For whom do the pages turn? They turn for me. Length is no deterrent when the words flow like melted butter. The ideas, the stories, the people, the places—all contribute to the full immersion of experience.

If I have to choose a set to honor, to recommend, to champion, each book in this collection of five can never be a mistake. And they are not the only ones for which it is so. It is not simply about enjoyment or like-mindedness. As I stated earlier, it is a marriage of objective quality in writing ability, storytelling, and transportation to other worlds, as well as interesting ideas, beautiful truths, deep connections between people, and the complexities of life and death.

This is not to say that each book is perfect. Perfection is not the aim. After all this time, I can say that with complete and utter confidence. Love is the aim. Insight. And growth. These books have all opened multiple dimensions to me, helped me grow, made me love, and urged me to shout about it.

So for now, these are my top picks for the Great American Read. Is it taking the easy way out not to choose a final top book? I would say the books that move me most are Outlander and War and Peace. In Cold Blood being a close second. Is it predictable to choose Outlander as my favorite book when it’s so clear from my blog that it’s at least well beloved by me? I love Gulliver’s Travels and Brave New World for similar reasons between them; they’re both science fiction, satire, mirrors up to their readers, and deliciously humorous, disturbing, deep, broad, and complex in proportions. They are classic epics.

All but Outlander delve deeply into social commentary on a broad scale (all but War and Peace done fully indirectly, through the story itself), though Outlander is not without indirect social commentary of a more specific nature. None but Outlander indulges in the pleasure of the human sex act. The novel is the most intimate, most personal, and in some ways, most vivid of these five. Certainly the most relatable.

War and Peace is likewise detailed and relevant to our struggles. In Cold Blood focuses on a crime, a pathology of human nature, on social dynamics and psychological dimensions. They’re all amazingly written, some in distinct writing styles. Outlander has the only female protagonist and first-person narrator, authored by a woman. These things elevate it further in my esteem. They say it’s quite difficult to write first person well, for example.

The humor and beauty, the terror and horror, the allure and fascination, the sheer intelligence and wit, as well as the greatly physical and emotional parameters, plus supernatural, science fiction, historical, mystery, romance, and action adventure aspects combine with all those elements previously mentioned to hoist Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander upon the shoulders of all the others. Its contemporary feel increases its relatability while its rich, exquisitely researched exploration of 18th-century Scotland helps anchor it further as a modern classic.

So, yes, I’m choosing one book, Outlander, for my favorite book, at least so far. I recommend this novel to most adults who have not become so totally ensnared in the cycles of pop fiction as to avoid all greater journeys.

As for the Great American Read, voting ends at midnight on October 19; results will be revealed by PBS on October 23. It’s really almost a moot exercise to pick a single book out of all 100 finalists, though. In a future post, I’ll caution against time wasted on some of what I felt were lesser choices among the 100, but again, I’m not a true expert, having not read all 100 books listed.

Meanwhile, if you don’t quite get to read Outlander before November 4th, the date of the Season 4 premiere for the STARZ TV series based on Gabaldon’s works, you’ll still have plenty in the books to explore. For this and so many other reasons, I recommend Outlander, the first in a soon-to-be-nine book series, by author Diana Gabaldon.

If you liked this post or want to learn more about why Outlander‘s the one, see my more comprehensive review at Book Review: Outlander by Diana Gabaldon. This blog also provides 3 Quick Book Reviews of the first three books in the series.

If you’ve read it and love it, I can only hope you’ll #VOTEOutlander on Twitter and Facebook, and select it today–only two more chances left!–online and by phone via the official Great American Read voting page.

See my post about the results, America’s top choices for the Great American Read.